The murder trial that put Kazakhstan in the dock

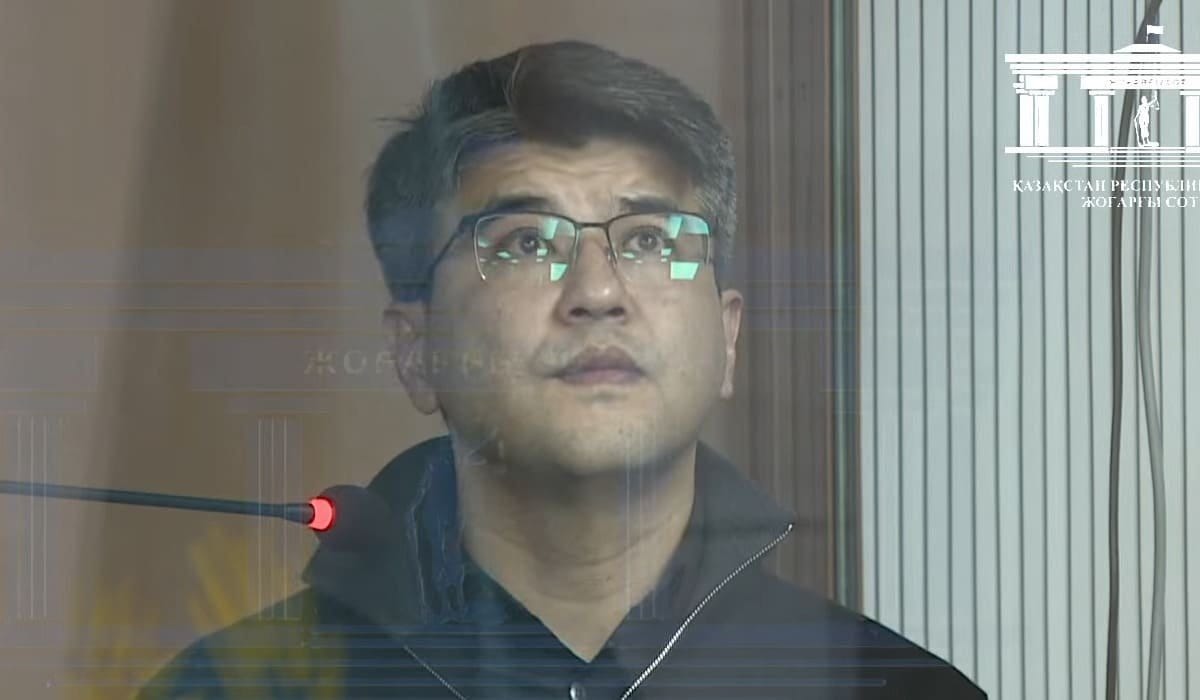

The murder trial of Kuandyk Bishimbayev, a one-time government minister accused of killing his wife, is being closely watched. The case has sweeping implications for Kazakh society.

The murder trial of Kuandyk Bishimbayev, a former top-ranking minister in Kazakhstan accused of beating his wife to death, has played out as tawdry soap opera.

Hundreds of thousands tune in daily to watch live streams from the court in Astana.

Jurors have heard how Bishimbayev systematically abused Saltanat Nukenova until he finally went too far one Novem…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Havli - A Central Asia Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.