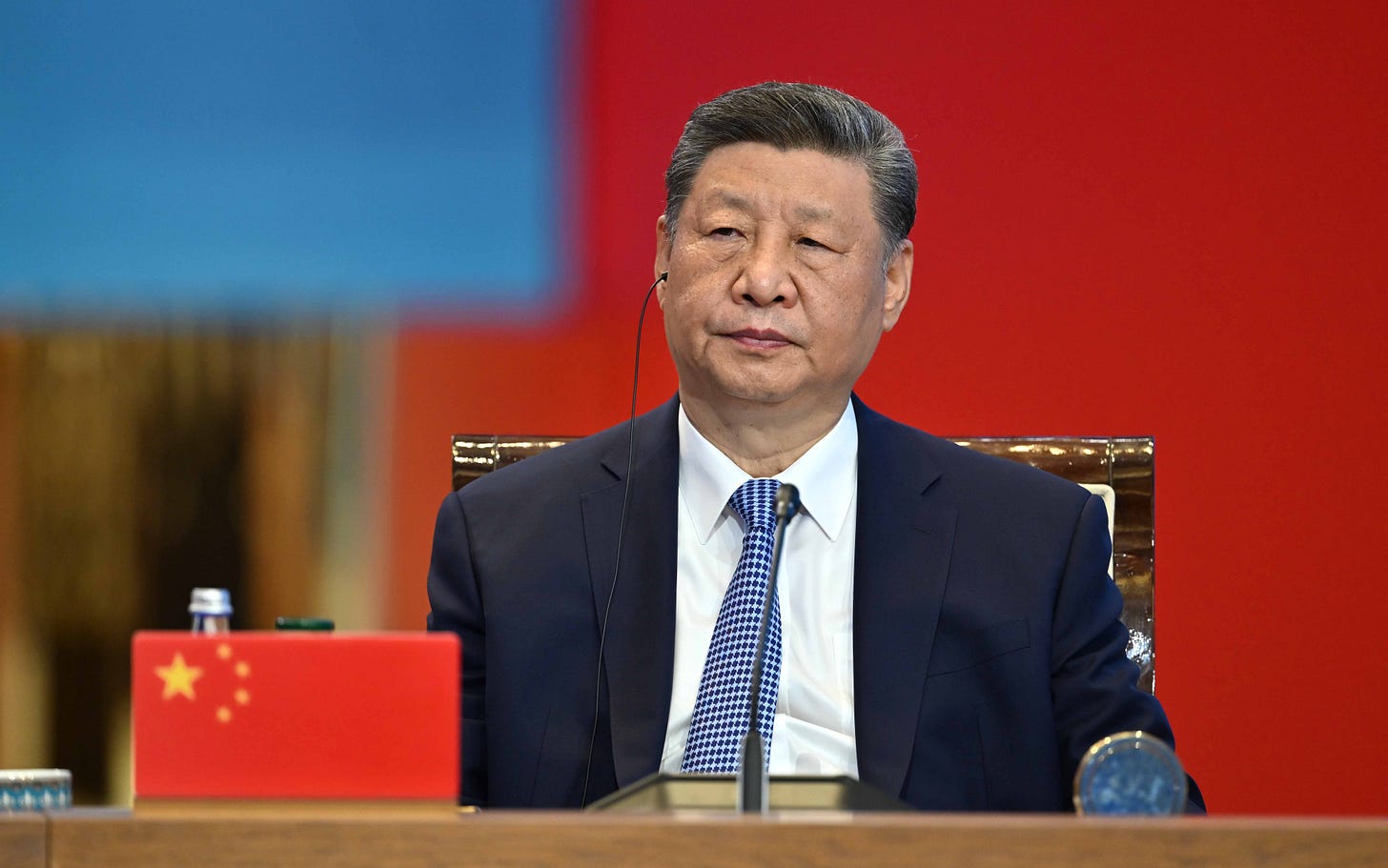

Isn't Xi lovely?: China’s strategic spend in Central Asia

Beijing pledged cash and connectivity at the China–Central Asia summit, while the region's presidents reached for buzzwords and bonhomie.

China summits are a smorgasbord.

Part infrastructure expo, part values manifesto, part investment pitch. All served in a single sitting.

But cold hard cash is the dominant dish. There is so much of it being bandied around.

Summoning his inner Oprah, Chinese leader Xi Jinping doled some out in his speech…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Havli - A Central Asia Substack to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.